Hey, White Clinicians: We Need to Address our Client’s Racial Resentment

Never Discuss Politics? Outdated Guidance in Counseling

As mental health clinicians, we’ve mostly been trained to separate ‘political’ beliefs or opinions from therapeutic discourse, ensuring we do not treat clients differently based on those beliefs, and avoiding imposing our own values (an ethical mandate of all mental health professionals). However, in our effort to keep politics out of therapy, we’ve largely been blinded from seeing that what are labeled ‘political opinions’ are sometimes cognitive distortions.

Discriminatory Beliefs Also Harm the One Who Harbors Them

We know racism and other discriminatory ideologies inflict profound harm on those who are the target of these beliefs. But what about on those who hold the beliefs? Research suggests that racial resentment and other discriminatory beliefs can have profound negative health effects on the individual who harbors them.

People who have these beliefs experience heightened levels of stress and anxiety, based off perceived threats to status. Those who have racist and other discriminatory beliefs suffer worse physical health, with more chronic disease and higher mortality. These ideologies can contribute to emotional turmoil, social isolation, and an increased susceptibility to rigid cognition and conspiracy thinking, fostering a distorted perception of reality.

People who have these beliefs experience heightened levels of stress and anxiety, based off perceived threats to status. Those who have racist and other discriminatory beliefs suffer worse physical health, with more chronic disease and higher mortality. These ideologies can contribute to emotional turmoil, social isolation, and an increased susceptibility to rigid cognition and conspiracy thinking, fostering a distorted perception of reality.

Racial Resentment and Voting Against One’s Self

Racial resentment and other discriminatory beliefs harm those who harbor them in another way: leading people to vote in ways that undermine their own interests and wellbeing. For example, white working-class Americans have repeatedly voted for leaders who restrict their healthcare access, suppress wages, and defund public education for their children. A key driver of this pattern is the false belief that racial progress comes at a personal cost. This zero-sum mindset—the cognitive distortion that gains for one group must mean losses for another—is a cognitive distortion well-documented in psychology. Racial resentment is often responsible for white people voting for elected officials who implement policies designed to marginalize communities of color; but these policies also trap millions of poor white Americans in economic hardship. In a well known example, opposition to Medicaid expansion, often fueled by racialized fears of so-called “handouts,”disproportionately harmed low-income white families.

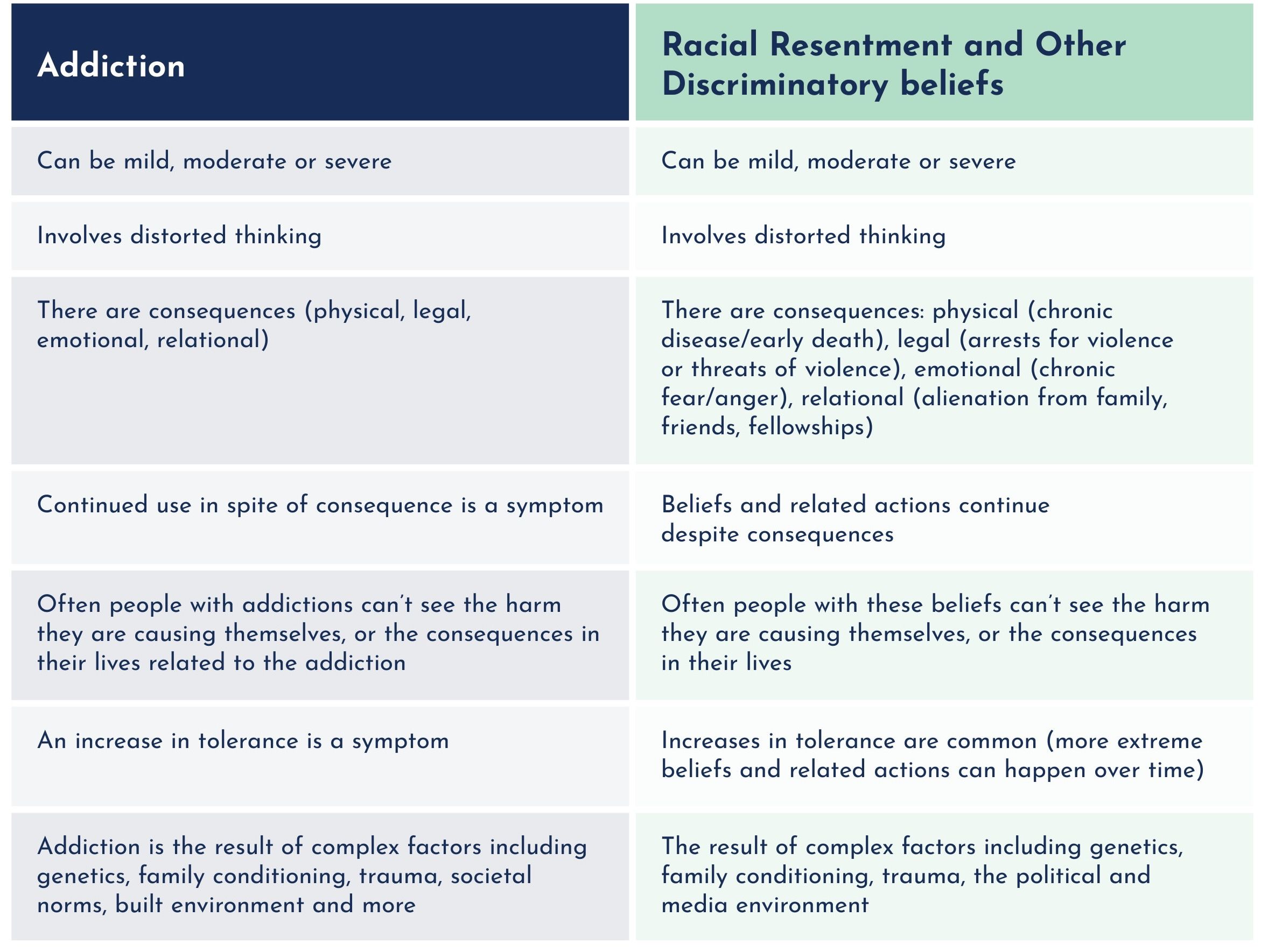

In understanding how we might address racial resentment, it can be helpful to conceptualize it as similar to an addictive disorder. The table below identifies the similarities.

We can look to addiction treatment, for how to address racial resentment as well. For example, once we begin to understand that our client might have a substance use issue, we don’t confront, challenge, or advise; we also don’t ignore. Similarly with racial resentment, once we begin to understand our client struggles with this, we don’t confront, however we don’t ignore. Just as we would with a client with an addictive disorder that they can’t see clearly, we:

We can look to addiction treatment, for how to address racial resentment as well. For example, once we begin to understand that our client might have a substance use issue, we don’t confront, challenge, or advise; we also don’t ignore. Similarly with racial resentment, once we begin to understand our client struggles with this, we don’t confront, however we don’t ignore. Just as we would with a client with an addictive disorder that they can’t see clearly, we:

- Develop a strong therapeutic alliance built on trust and empathy.

- Gently elicit self-reflection and insight about the impact these beliefs have on their emotional and physical wellbeing. I once said to a patient, who had become increasingly angry as she shared with me how much she resented a particular ethnic group, and wished they were not part of the US “I can see how angry you are right now, just sharing this with me. How is it for you, to feel angry like this?” which led to a dialogue of how much stress the resentment was causing her, as well as where it came from. It was a beginning.

- Develop Discrepancy: Most people have values that are at odds with discriminatory beliefs and racial resentment. We can develop discrepancy by gently highlighting the incongruence between the client’s stated values (such as fairness, kindness, or integrity) and their discriminatory beliefs or behaviors. This involves asking open-ended questions that encourage self-reflection, using reflective listening to deepen awareness, and reinforcing moments where the client expresses more inclusive or compassionate perspectives.

- Explore with clients what underlies the anger. Anger is usually a secondary emotion, covering fear, shame, hurt and other feelings. If we can get to the underlying, more vulnerable feeling, we can get below the distorted thinking, and often help resolve the resentment.

- Avoid judgment, confrontation, or arguing, which can further entrench the belief and behaviors, wound the therapeutic relationship, and inhibit our ability to help.

Addressing Concerns About Political Bias

Some of us may fear that addressing these issues means pushing a political agenda. (I know I worry about this). And yet, to continue to ignore this thinking patterns that cause so much harm now seems clinically irresponsible. To address the concern that we might be pathologizing political opinions, or pushing our own values on clients, we can:

- Approach the work with humility, caution, and empathy.

- Engage in consultation with trusted colleagues.

- Prioritize gentleness in raising awareness, just as we do when helping someone who isn’t yet able to see the damage their addiction or cognitive distortions are causing them.

By reframing discriminatory beliefs as harmful thought and behavior patterns, rather than mere political opinions, we can help clients break free from cycles of manipulation and suffering in their own lives, while also reducing harm to those who are the targets of their resentment.